Taylor Swift’s You’re On Your Own, Kid is my favourite pop-culture exploration of Satanic psychology. Since I basically now use this as a general fandom blog, and since Miltonian Satanic stuff is at least something of an influence on 40k’s general writing and vibe, I will write about why here! I think we all know that Taylor Swift x 40k is the crossover the world has been waiting for.

So what’s the song about? You can find the lyrics here, though I personally do not think the annotations do a good job of capturing the spirit of the song. The basic events recounted are: the narrator (who we can assume is Swift herself, though of course a fictionalised version thereof) gives us three snippets of moments in her life when she had an important realisation. The first verse, when she is young in a small town dreaming that some boy will notice her and reciprocate her feelings. But one day while “search[ing] the party of better bodies” she realises that he doesn’t care for her at all - perhaps she confesses her feelings and is rebuffed, perhaps he makes it clear that he is with someone else, perhaps he is cruel in some way; doesn’t matter, in any case she now knows he has no feelings for her. The next snippet concerns Swift’s emerging musical talent; she resolves to make it out of her town by pursuing her artistic career, and initially she’s a big deal in this small pond. But the moment of realisation occurs when she is trying to hit the big time and in some new environment she once again finds herself searching a party full of better bodies and this time it strikes her: “your dreams aren’t rare”. She’s just one of a million pretty young women who wants to be a pop-star, why should she be chosen over them? In both cases she immediately follows the revelation with the summary “you’re on your own, kid”, and the chorus refrain is “[f]rom sprinkler splashes to fireplace ashes” - the feeling we get is that each revelation is her coming to appreciate in some new way that from start to end (here visualised as hopeful sprouts being nurtured all to end in flames) she is, in fact, the only person who actually cares about her, the only person invested in her ambitions for herself.

So we go into the last snippet. It reads:

From sprinkler splashes to fireplace ashes

I gave my blood, sweat, and tears for this

I hosted parties and starved my body

Like I'd be saved by a perfect kiss

The jokes weren't funny, I took the money

My friends from home don't know what to say

I looked around in a blood-soaked gown

And I saw something they can't take away

'Cause there were pages turned with the bridges burned

Everything you lose is a step you take

So, make the friendship bracelets, take the moment and taste it

You've got no reason to be afraid.

What’s going on here? Well, I think a couple of things, basically corresponding to the first and second half of the verse. In the first half we get a contrast between the relationship of the first two verses. The transition from the first into the second verse was basically her finding that she was being rejected by the man whom her ambitions had centred upon, probably due to all those “better bodies” making her insecure, so giving up on those ambitions. Whereas here she has once again found that between her and her ambitions stand lots of better bodies threatening to outcompete her - but she has stood her ground and fought, become the host of those parties, starved herself until she had a body that might be good enough, that would get her the kiss. But more than just that; she’s abandoned everything that made her who she was, all in the service of achieving this goal. Her integrity was sacrificed for this ambition, she was willing to do whatever it took. The realisation comes re what this says about her and her life as she looks around in a (hopefully!) metaphorical “blood-soaked gown” at what has become of herself for all this.

But, and here is where it gets Satanic, the lesson she draws from this is a kind of dark-mirror Stoicism. She realises that having sacrificed everything that mattered to her in service to this ambition she’s therefore escaped the cycle of hope-then-disappointing-realisation that characterised the previous two verses. Because she has nothing left to hope for; she has nothing of herself left at all, nothing that could ground that kind of aspiration. But with nothing to hope for, she has nothing to fear. She can live in the moment! Sure, she’ll “make friendship bracelets” - things meant to signify long-term commitment - but she does so secure in the knowledge that, of course, she has no long term commitments, everything is ultimately subordinate to a dream that no longer means anything to her, which means she no longer has to worry about the end of the friendship. You can’t betray commitments if you never really have any, you can’t lose friendships you never really posses. If freedom’s just another another word for nothing left to lose then, well, she’s free; with everything that entails.

The song ends on this droning discordant note. It’s uncomfortable. We have achieved resolution, of a sort, but not catharsis. It’s asking us to consider whether the kind of happiness and acceptance Swift finally finds is actually an appropriate place to end up at all.

I find the the psychology behind this song fascinating. It reminds me of Milton’s Satan. (Paradise Lost is one of my my favourite texts ever and very influential on my life trajectory; my nerdy rebellion as a kid was telling people I was going to study for exams but actually going to the library and reading various works of sci-fi and classic literature. Paradise Lost is a text I read during that odd teenage pseudo-rebellion, and it imprinted itself upon me.) There’s a famous moment in Book IV of Paradise Lost wherein Satan, having escaped the physical confines of hell, makes it to Eden - a garden of delights, a literal paradise - and finds of himself that he is still miserable. He introspects, and come to the realisation that the problem is internal, it’s his psychology that is the true hell, not the superficial physical torments and miserable surroundings of hell-the-place. As he puts it:

Me miserable! which way shall I fly

Infinite wrauth and infinite despair?

Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell;

And, in the lowest deep, a lower deep

Still threatening to devour me opens wide,

To which the Hell I suffer seems a Heaven.

Which prompts him to consider whether maybe, just maybe, he might have made some mistakes along the way to becoming someone who could be miserable in Eden. After considering and rejecting the possibility of repenting, he concludes thusly:

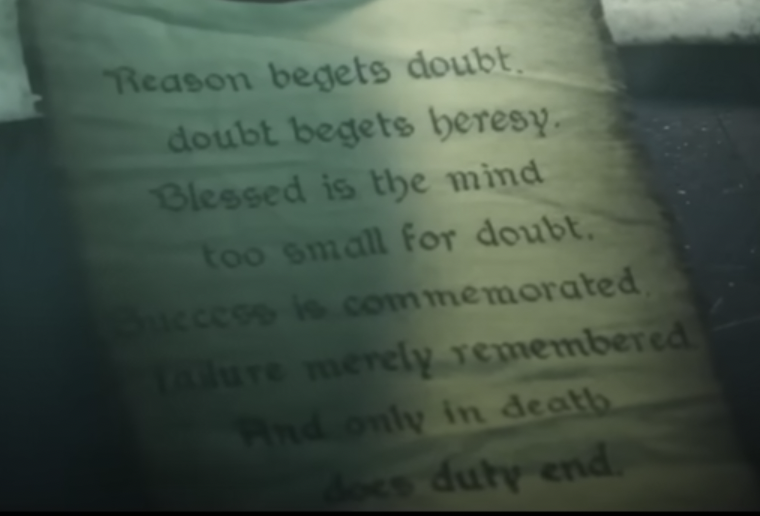

So farewell hope, and, with hope, farewell fear,

Farewell remorse! All good to me is lost;

Evil, be thou my Good: by thee at least

Divided empire with Heaven’s King I hold

And I think I see in Swift’s song the same psychological movement that Milton depicts Satan as going through. This is a moment where Satan steel’s himself, he resolves to action (successfully, sort of — in that he rather famously will in fact succeed in corrupting mankind) and finds the strength to carry on. But that inner “strength” actually comes from an utter hoplessness, a nihilism so profound, that it strengthens just by removing anything that might count as a cause for fear. Someone who is in hell no matter what happens anyway cannot be threatened, cannot be offered anything good either — whatever purpose they happen to find themselves with, they may as well see it through for simple lack of anything able to sway them against it.

(The link to 40k, by the way, is that I take it this is meant to be some of the Traitor Legion’s motivations for continuing the long-war against the Imperium. Horus is obviously meant to be a Satan figure; not just in the religion of the Imperium but also in the narrative of the Horus-Heresy book series. And I think at least some of his legions are meant to be continuing a fight whose purpose and meaning has been long lost for something like this reason. Plenty of them, after all, do not actually worship chaos, they have no investment in the religious ideology or serving the hell-gods. Yet all the same they literally live in hell, they have nothing to lose and nothing you can really threaten them with nor bribe them with, no inner humanity left to appeal to; all they have is the nihilistic will to ruin that which they associate with their downfall, fulfilling some ambition whose meaning has long ago been lost to them.)

And this is where I think Swift is suggesting she finds herself at the end of You’re On Your Own, Kid. At one point the ambition meant something to her; it was a way of escaping her town, proving herself worthy of being noticed and loved in a way she had not been there, and expressing something meaningful through her art. But to actually get there she had to become someone for whom the art didn’t mean something, was not worthy of love; and while, sure, she wasn’t in her home town anymore — in general she just wasn’t forming meaningful connections, so it doesn’t ultimately matter where she is. But rather than seeing this as a reason to change up, to abandon course, she draws a kind of strength from it — now, unlike before, she cannot be disappointed, she’s escaped the cycle of saṃsāra by becoming someone to whom nothing matters at all. So now, sure, she can continue pursuing that goal, she can “enjoy” the varied experiences life sends her way, free from all fear. Free from all joy too.

In philosophy we debate whether anyone ever knowingly does evil. Socrates, famously, maintained they do not - and was memorably confronted on this by Callicles (another character who has imprinted himself on me). Socrates is, in the end, unable to persuade Callicles. This is not just a quirk of the characters in this moment: the deeper point is that Socrates' methods of persuasion actually require that he is right on this very issue - they require that you care, that if you realise you’re wrong that’s reason to correct. Callicles genuinely and consistently does not, and simply checks out of the conversation when it is dull to him. We’re left with a similar tension, a similar discordant note - can this really be it, can you know that you’re in the wrong and act anyway? A student has got me thinking about this lately, because she takes very seriously the possibility that people can. Somewhat unreflectively I have gone through life assuming Socrates was right, that when we persuade people they are wrong that will cause them to think or behave differently. But the Calliclean/Satanic/Swiftian response is at least conceivable too, and as I look around the world I worry that my student may be right after all.